Chances are you’ve received a text message like this.

Scroll down

Most likely you just deleted it.

But have you ever wondered who's sending them?

We're going to take you inside their world.

Scam Factories

The inside story of Southeast Asia's fraud compounds

Ben Yeo is trapped in a scam centre in Cambodia, desperately trying to escape. It's early 2024 and he's been here for 30 days.

Thirty days since Ben and his wife Moira realised their well-paid new casino jobs were just an elaborate ruse.

Now they have to choose: pay their captors a US$20,000 ransom or get to work in the scam compound.

Walking into a trap

Malaysian-born Ben had worked for years as a consultant organising government investment conferences in Cambodia and Myanmar.

When his freelance work dried up, he and Moira started looking for permanent roles.

They saw a recruitment agency was hiring staff for a casino in the town of Bavet, near the Vietnamese border.

Ben did some research on the company and everything seemed to check out. It was registered and had a recruitment licence from the Cambodian government.

They both negotiated new jobs, Ben doing business development and Moira as a card dealer in the casino.

From the moment they arrived at the compound, Ben had a bad feeling. Then his new employers told him he wasn't allowed to leave.

Ben and Moira aren’t alone. Experts estimate there are hundreds of thousands of scammers in the industry across Southeast Asia. Some of them are unrepentant criminals, ruthlessly exploiting victims across the world. Others are victims themselves, trafficked and held against their will. Others still are desperate people willing to participate in the industry to survive, but once inside, find they can no longer leave.

Scam Factories is a special multimedia and podcast series by The Conversation. Listen to the podcast series here.

On the trail of the scammers

We've spent the past three years interviewing these people to understand their motivations and the inner workings of the booming scam industry.

We've spoken to nearly 100 survivors from compounds mostly located in Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar. We've also interviewed local and international civil society organisations, policymakers and law enforcement throughout Southeast Asia.

Because the industry is hidden behind high walls mounted with barbed wire and surveillance cameras, we’ve also spent countless hours tracking the scammers online.

We've scoured Telegram channels and messages, online job advertisement websites and social media platforms to understand how criminal groups lure people into the industry.

And we gathered a wealth of data through years of observing the power networks and money flows that underpin the industry.

Everybody's situation is different. Every story of how they got trapped varies.

Alongside our research partner, Mark Bo, we will be publishing a book in mid-2025, Scam: Inside Southeast Asia’s Cybercrime Compounds.

Predators or prey?

Those who become trapped in the compounds come from all walks of life. Many scammers from mainland China are what Chinese authorities refer to as "san di" ("three lows"), meaning they have low income, education and age. Desperation drives them to the industry. As one former scammer told us:

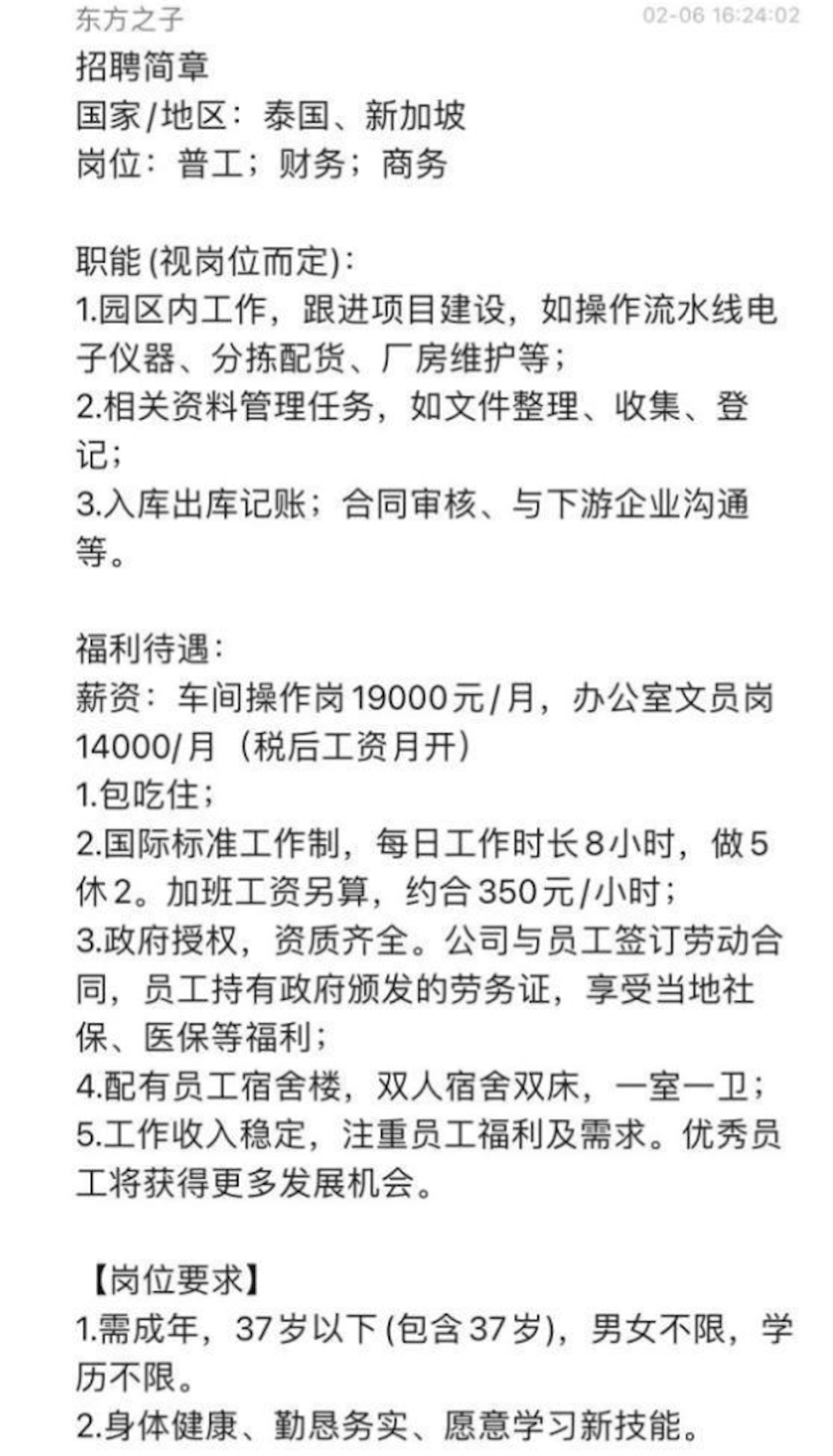

Many are lured by vague-sounding ads on job recruitment websites or social media, while others are directly targeted.

Telegram is a popular platform for recruiters. The jobs often sound like legitimate opportunities in customer service, sales or promotions. Some ads, though, are for jobs in sectors as diverse as construction, food and tourism. Recently, a well-known Chinese actor was even lured to Thailand for a fake movie casting call and ended up in a Myanmar scam compound.

A Chinese actor reported missing at the Thailand-Myanmar border has been found after fears that he might have entered a Myanmese city known as an online scam hub. Read more: https://t.co/sSxZVOZG3R pic.twitter.com/WZFsVU0kcR

— South China Morning Post (@SCMPNews) January 8, 2025

Functions:

1: Work within park and follow up on project construction

2: Information management, file sorting, collection, registration

Salary: workshop position ¥19,000 a month

1: Food and accommodation included

2: Standard working system, 8 working hours per day, 5 days of work and 2 days of rest

3: Government authorisation... The company signs a labor contract with the employees [for] local social security, medical insurance and other benefits

4: Equipped with staff dormitory building

5: Stable work income, focus on employee benefits and needs

There are often promises of high salaries, year-end bonuses and promotion opportunities. Yet, many ads have minimal skill requirements, such as basic computer literacy and fluency in a specific language. This is a red flag. As is the offer to cover food, accommodation and travel expenses.

Others are tempted into the industry through brokers, who may spend months building personal connections with their victims before approaching them with an “unmissable” job opportunity. These brokers are typically paid a fee by the scam company, which then becomes a debt the victim or their family must later pay to secure their freedom.

Some are duped by people in their social circles, friends or even relatives. Other victims are kidnapped right off the street. During the pandemic, out-of-work gangsters turned to kidnapping people for scam operations to make a living.

Punishment and manipulation

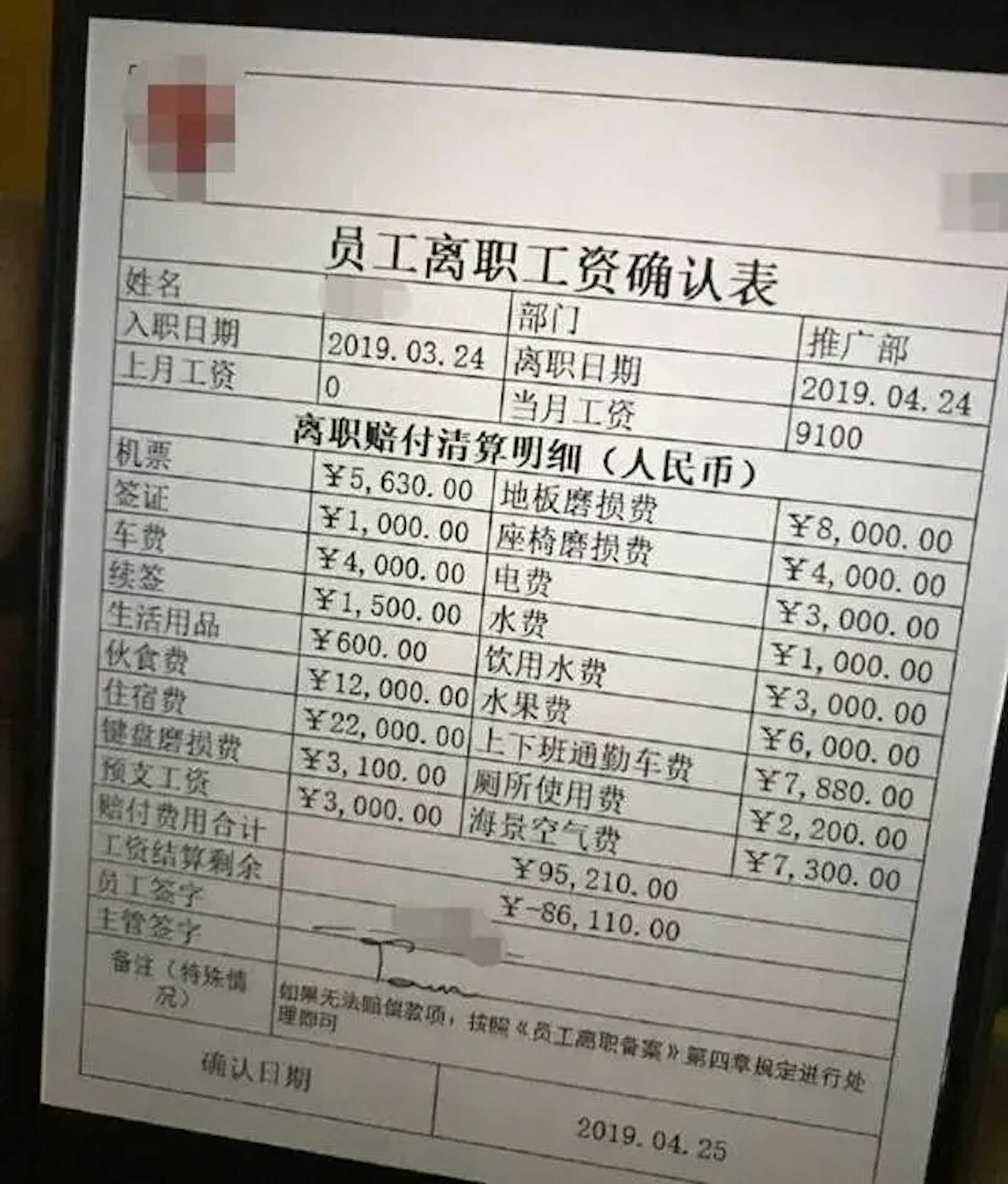

Victims often begin their new "jobs" with a massive debt for flights, visas, permits and broker or trafficker fees.

These debts grow the longer they are held, with accommodation, food and even "seaside air" added to their final bill.

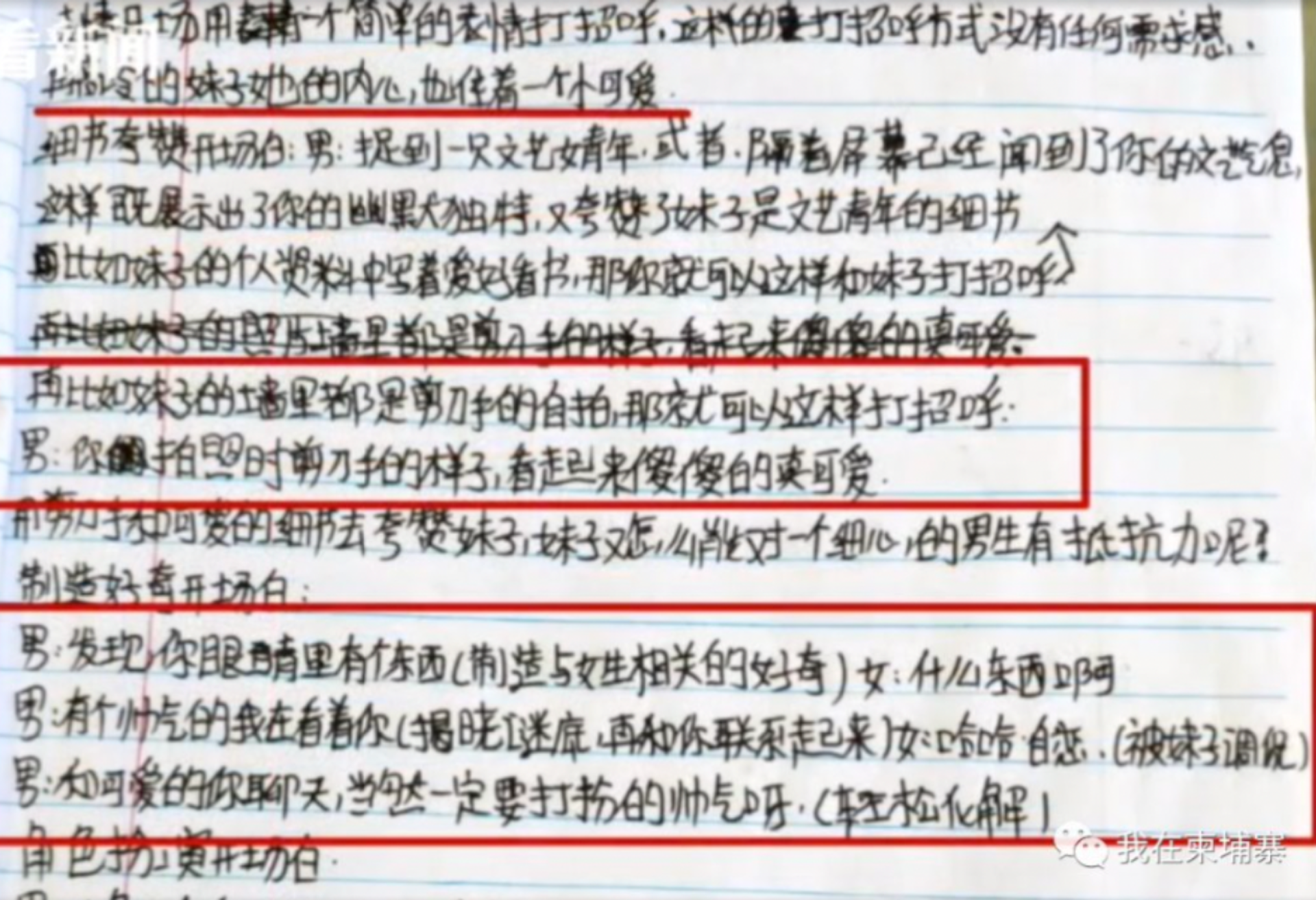

Newcomers must also be instructed in how to pull off a scam. Some are highly scripted frauds that require intensive training and dedicated phrasebooks.

Approaching a scam target and earning their trust can sometimes take months. Here's how one scammer first ensnared a woman in China over WhatsApp, texting daily and presenting himself as a successful cryptocurrency investor.

In many compounds, the scammers work long shifts, sometimes as many as 17 hours. Some begin their day shouting a slogan, such as:

But very few actually "win". Their performance benchmarks are extremely high. One employee in a Cambodian compound told us they were expected to generate US$10,000 in revenue each month and entice two to three new victims a day.

The most successful employees are held up as models. One former scammer told us it's akin to brainwashing.

For those who cannot meet their targets, life quickly becomes a nightmare. They can be beaten, subjected to electric shocks and even have their nails extracted.

Sexual violence is rife. Alice, a Taiwanese woman using a pseudonym, told us that when she refused to engage in scam work, she was sold numerous times between compounds and repeatedly raped. Before she was finally rescued, the gangsters threatened to lock her up in a brothel-like clubhouse at a scam compound to serve at the pleasure of the managers and workforce.

Male victims are also forced to perform sexual acts on each other as a form of punishment.

Another harrowing aspect of life inside the compounds is the potential to be sold like a slave to the highest bidder. We have heard of skilled workers fluent in Mandarin fetching anywhere between US$10,000-30,000.

Freedom, finally

Despite Ben's pleading text messages, his family refuses to pay the ransom. As punishment, he is separated from his wife and locked in a room by himself.

Moira and Ben were held at a police station with other scam compound survivors. Source: Ben Yeo

In desperation, Ben's family approaches the Malaysian embassy in Cambodia seeking help. Eight days later, police arrive at the scam centre.

But Ben and Moira's ordeal doesn't end there. When they give their statement to the police, they notice that someone from the scam compound is in the room. Ben notices the written statement doesn't include any mention of the abuse they suffered. He's sure the police have been infiltrated.

With the help of an influential family friend in Cambodia, they're transferred to another police station. The scam company follows them there, too. This time they are offered a bribe in exchange for their silence.

For weeks, Ben and Moira are subjected to questioning by Cambodian authorities.

Eventually, they are released by the police and taken to a shelter run by a charity. But even then, the anti-trafficking authorities try to paint them as criminals. After three months there, they're finally told they'll be returning home. But only if they sign a document agreeing not to pursue charges against their captors.

In part two of our series, we explore how scamming exploded overnight in Southeast Asia to become a multi-billion-dollar industry.